Last week, we took you on a day trip away from busy and noisy Madrid to the tranquility of Aranjuez. But peace and quiet are not the only things that you will struggle to find in Madrid. The city’s history, too, is short of a register or two.

Madrid overflows with the Baroque glory of Spain’s Golden Years but does not have what gives Spanish cities their characteristic flavour: the urban jungle mix of densely packed streets from the Middle Ages …

… in which you can hear the echo from 800 years of Muslim rule.

Modern Madrid does not have an obvious Islamic heritage – but this is not, as some visitors might think, because the city was never under the control of Spain’s Muslim conquerors.

In fact, Madrid – like most of Spain at one time or another – belonged to El Andalus but never achieved a status higher than that of a small garrison town.

When the modern city took shape in the late 16th century, the Islamic Caliphate of Spain was a thing of the past: embedded in the national memory, although the country’s rulers from the Habsburg and (later) the Bourbon dynasties were looking elsewhere for inspiration of how to build their shiny new capital.

So while Madrid may be short of alluring exoticism and medieval townscapes, the good news is that you can find these things a short train ride away.

Toledo has plenty of both …

… and, as a bonus, something else that you would not find in Madrid: a scenic, stormily romantic riverside walk just outside the town centre.

To create an interesting river trail, Madrid had to engineer some scenery around the rather boring profile of the Manzanares. Toledo had no need to engineer anything. Mother Nature had done that already.

And to further embellish the romantic theme, human hands have, over the centuries, added some picturesque structures and buildings, some of which have survived as even more picturesque ruins. Wordsworth would join his daffodils in a dance of delight.

For the best short walk in Spain, we recommend to follow this “city stretch” of the Camino del Tajo – the river trail continues from here 3.5 km further upstream – that starts a few hundred metres away from the train station. Turn right out of its main exit and, after the roundabout, follow the Paseo de la Rosa.

When this street takes a sharp left turn, do not follow the throng that crosses the Alcantara Bridge into town – or the smaller throng that is heading up the Carretera Alto for the viewing platform called the Mirador del Valle.

Instead, take the stairs that lead you down to the river Tagus (incidentally, the longest river on the entire Iberian peninsula), walk underneath the Alcantara bridge and cross over to the town centre on the next bridge, the Ronda de Juanelo. At the end of this bridge, turn left into the Ruta de Don Quijote.

The balcony view offered by this stretch of the historic trail is, if anything, even more breathtaking than the spectacle of the Camino del Tajo. And as the icing on the cake, you will – at the end of the walk – enter Toledo “through the back door”, which allows you to peek behind the curtain for a fresh and non-touristy perspective of the town.

To me, this is the Best Short Walk in Spain – and it will remain so until someone can convince me otherwise.

After this brief introduction to the charms of the Tagus Valley, you should approach Toledo’s narrow web of medieval streets in a spirit of serendipitous discovery. This is not a city where it would be a good idea to tick off one item after the other on an itinerary of churches and museums (of which they are many). Just soak up the atmosphere (of which there is much).

Toledo is often called the “Ciudad de las Tres Culturas”, but these three cultures – rooted in Christianity, Islam and Judaism – were never neatly separated but allowed to blend. There was, admittedly, a Jewish quarter …

… but even in the Middle Ages, Jews were allowed to live elsewhere and non-Jews (such as the painter El Greco) were welcomed inside the area between the modern Calle de Santo Tomé and Calle de los Reyes Catolicos.

Toledo has been a Catholic city for nearly 1000 years …

… but its predominant architectural style remains a mix, reflecting the cultural cheek-by-jowl of the town’s glory days.

One should not idealize life under the Islamic Caliphate, but the city’s different tribes clearly found a way of not being at each others’ throats 24/7. Toledo is a city of bridges in more ways than one.

The result may be unique, but what modern Toledo is not is the only Toledo in the world (there are 12 in the USA alone). It is not even the biggest Toledo: that honour goes to its namesake in Ohio, whose short-lived minor league ice hockey team was named the Blades, presumably a pun on the players’ footwear and the medieval arms industry that had once made the original Toledo famous across the old world.

The reputation of Toledo for sharp steel still reverberates, like so much else in this town, between the walls of its ancient buildings.

So you see: there is a lot of atmosphere to soak up, and complex itineraries will only get in the way.

We nevertheless suggest to take a closer look at two buildings, starting with the first one you will set foot in after your arrival, provided you are coming by train from Madrid.

Toledo’s train station, an element of modern city infrastructure that extensively references “Muslim” architecture, is less of an anachronism than it may seem: practically all “Islamic” architecture in modern Toledo was created by non-Muslims.

Toledo fell to Spain’s Christian coalition at an early stage of the reconquista, way back in 1085, but the country’s fondness for the architectural language of its Arab rulers clearly did not end with the Castilian conquest.

The “Spanish dialect” of this architectural language – the Mudejar style – emerged when the Islamic rule was still part of the country’s living memory and later, in the 19th century, evolved into the Neo-Mudejar manner for which Toledo’s train station is a beautiful example, blending different cultural influences as well as the ancient with the modern.

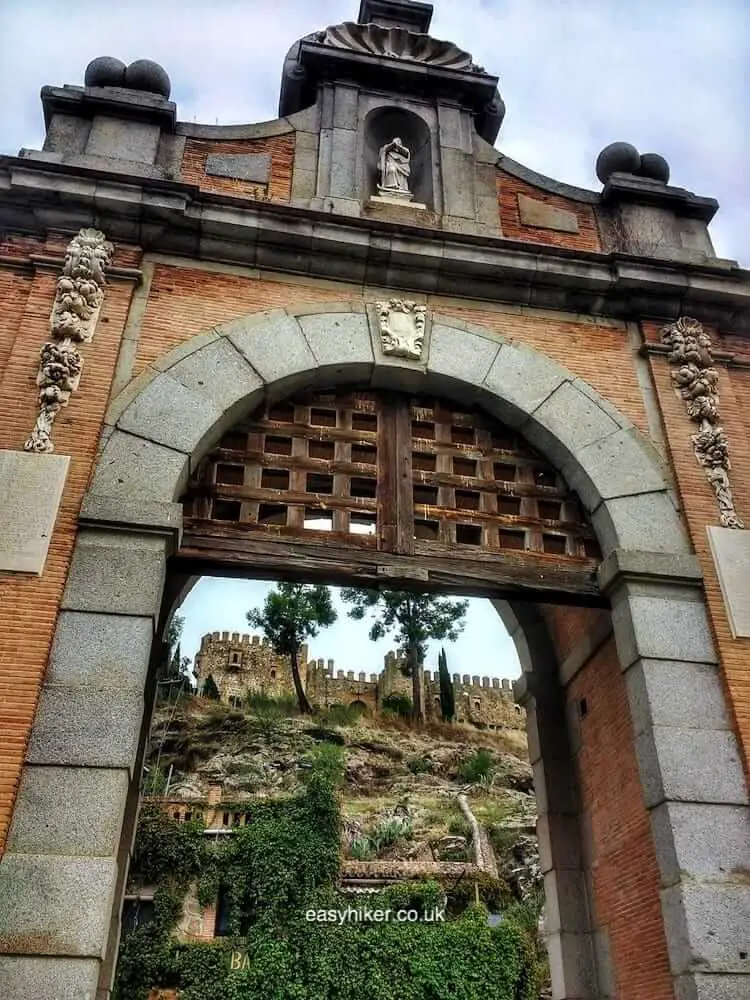

Secondly, you may want to take a closer look at the Alcazar, the 16th century fortress that hovers so menacingly over the old town. This building played a key role in the history of modern Spain and the Civil War of the 1930s.

When the left-wing government took over in 1936, Jose Moscardo, the commander of the 1000-man-strong Alcazar garrison, sided with General Franco’s rebellion and barricaded himself and his men in the fortress, refusing to take orders from Madrid.

Following which the Republican fighters arrested Moscardo’s young son and threatened to kill their hostage unless the commander surrendered.

Presumably in the belief that this would soften the commander’s resolve, the Republicans then allowed Moscardo to communicate with his son over the phone, but he only told young Luis to “commend his soul to God” and “die like a patriot”. Luis was shot on the same day, and Moscardo held out for 70 days until the fortress was relieved by pro-Franco units, a key turning point in the Civil War.

Moscardo went on to wear a black cloak over his uniform for the rest of his life (he died in 1957), in memory of the tragic dilemma he had been facing and the terrible sacrifice his family made.

It is stories like this that have made it such a struggle for Spain to develop a formula of post-civil-war reconciliation. Could it be that a solution will be found in Toledo’s wider history – and that a recipe which allowed three cultures to coexist might also serve to finally reconcile the two hostile tribes of Nationalists and Republicans? There is still hope for the wound that appears to never heal.