If it is true that geography is destiny (as is often said), the slopes of the Val d’Aosta have always been fated to be stacked with castles.

The surrounding mountains make it difficult for a central authority to gain full control, while the valley’s remoteness from the power centres of its neighbouring countries (historically France and Savoy-Piedmont) favoured the emergence of an unruly class of aristocrats.

For centuries, quarrelsome nobles fought distant monarchs and each other, often at the same time. In the process, they inadvertently shaped the landscape’s unique character: while vertiginous rocks are one feature of the valley’s landscape, the castles that sit on top of them are the other.

The boom in the construction of fortified residences that caused such headaches for medieval kings benefits today’s visitors who can choose between a wide range of interesting day trip destinations.

While some of these castles are remote and you will need a car to visit them, the area’s public transport is surprisingly useful. For one, a train line runs through the valley – it is out of action until December 2026, but Trenitalia operates a very good coach substitution service.

On top of that, a regular bus service connects Aosta and Pont Saint Martin at the opposite ends of the valley. Line 110 – which starts from the Aosta Autostazione opposite the central train station – passes many of the most famous castles and, even better, circulates at near-metropolitan frequency, a bus coming roughly every 30 minutes.

Sit near a window and have your camera ready! You will take some blurry shots and photos of vaguely castle-ish outlines against dark backgrounds but also close-ups and interesting juxtapositions of historic and modern building fabric (this photo shows the town and the castle of Verrès).

Thanks to the efficiency of the public transport system, you could even visit more than one castle in a day – although I am not sure whether that would be a wise use of your time budget. Bear in mind that castles always promise more than they can deliver, not so much because what they deliver is of low quality but rather because they promise so much.

Nothing can possibly beat the feeling of first spotting a magnificently fortified palace proudly perched on a hilltop, particularly if this palace is framed by snow-covered peaks.

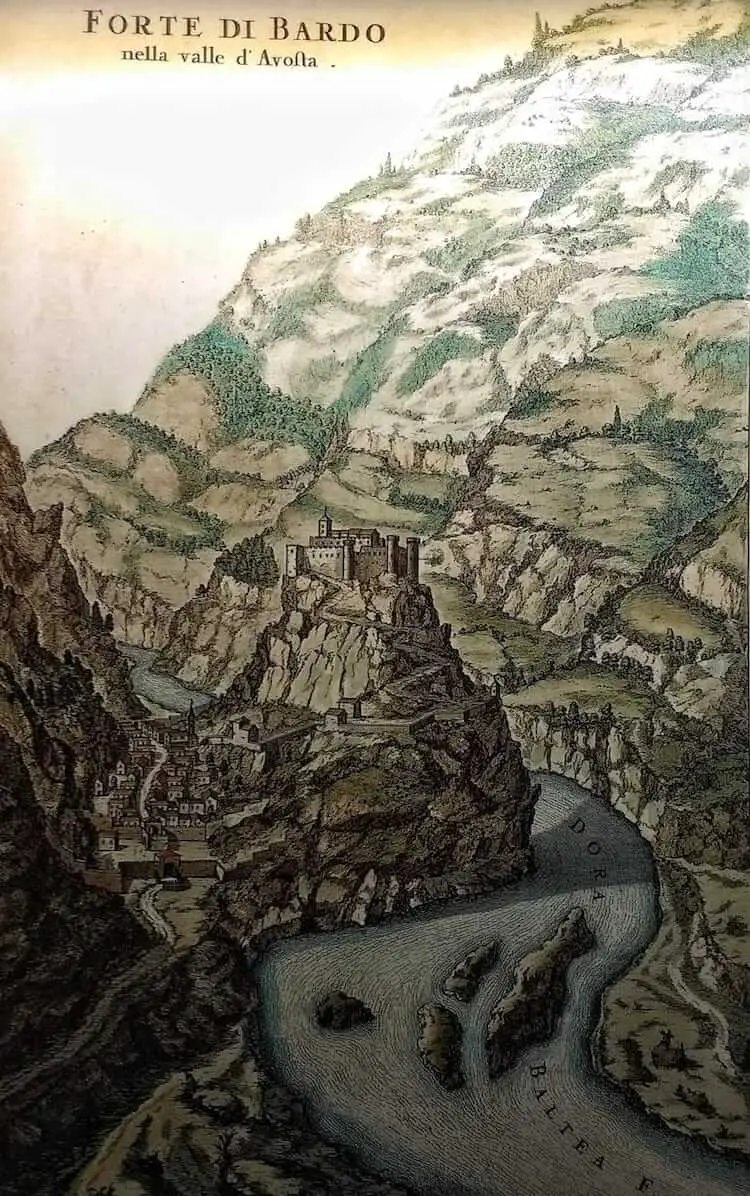

An excellent example for this mechanism is the Forte di Bardo, the rough beast of the Aosta Valley, which appears to pour down the cliff like molten lead, slouching towards Bethlehem to be born.

Bardo Castle, perched over the entrance to the valley, was of supreme strategic importance until the 19th century. It overlooked the valley’s narrowest point, and every invading army was forced to pass right underneath its feet. For a long time, this was the Bardo’s blessing, but eventually, it became its curse.

After Napoleon’s 40,000-strong army was held up on its march to Turin for two weeks by 400 soldiers inside the Fort, le petit Empereur was so annoyed that he had the medieval castle razed to the ground once his men had taken possession of it.

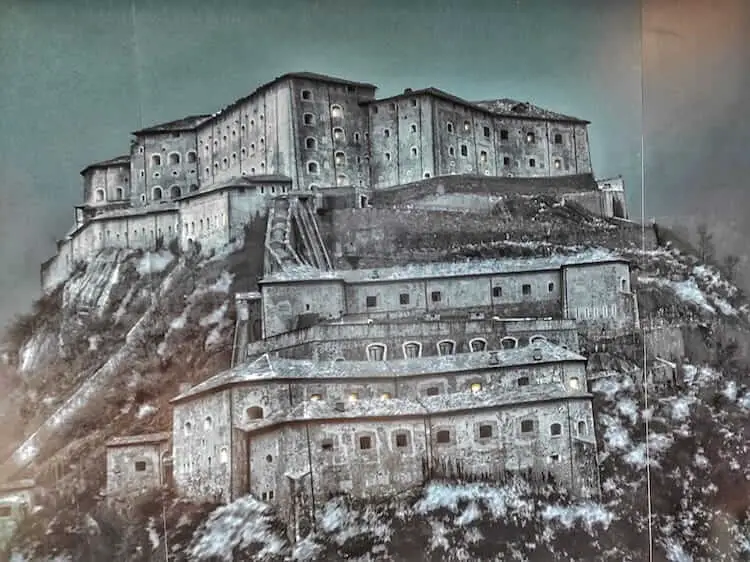

But even in that age of heavy artillery, the strategic importance of the Fort was considered so great (location, location, location!) that the Kings of Savoy had it rebuilt in the 1830s. This modern version, however, was no longer a mixed-use castle or fortified palace but a fortress pure and simple.

Today, it is easily the most forbidding structure in the entire Aosta Valley.

Inevitably, the Bardo’s appearance as the villain’s lair from central casting did not escape the attention of Hollywood. Since the completion of extensive restoration works in 2006 (before which the castle had been closed for decades), it has already featured in several film and TV productions, most famously as Novi Grad, the capital of the (fictitious) Eastern European rogue state of Sokovia, in Avengers: Age of Ultron.

The regional government (which owns and runs the Forte di Bardo) seems to be rather proud of its building’s notoriety and has dedicated a small permanent exhibition to commemorate the castle’s brush with Hollywood glamour.

What else is to see in the Forte?

Since the rebuilt Bardo has never served as an aristocratic residence, there are no historic items of furniture or objets d’art on show. The authority that runs the place makes that up through a range of exhibits (the Bardo also doubles up as the official Museum of the Alps), but there is no denying that the building’s interiors follow their military function and, as a consequence, are rather austere.

From the castle ramparts of the rough beast of the Aosta Valley , however, you do get magnificent views into the valley and the surrounding mountainside – as well as the occasional peek at a sure-footed gardener.

Another fascinating part of the visit is the walk from the bus stop right at the foot of the castle up the ancient high street of the medieval Borgo di Bardo. Until the middle of the 19th century, when the modern road by the river was built , this street – the ancient Roman Via delle Gallie – provided the only route through the canyon. Not only invading armies: everybody who wanted to enter or exit the valley – merchants, pilgrims, journeymen – had to pass through Borgo di Bardo. As a consequence, the Borgo was the most important village in the entire Val d’Aosta.

Since when the Borgo has lost its central role in the local economy and most of its inhabitants, too (only 134 of whom were left at the last count).

What the Borgo has not lost, however, is its medieval character. The village has been well preserved, and information panels along the high street provide you with fascinating insights into the village’s unique history.

It seems also fair to say that the Borgo di Bardo offers something you don’t get inside the fort: a proper period atmosphere.

On our way back to our holiday base in Aosta, we decided to pay a brief visit to the small town of Chatillon, which had looked interesting from the bus on the way in. It turned out to be not all that interesting, although it has its scenic moments.

It also did not help that it was August and we arrived at the mad-dogs-and-Englishmen-only hour when nearly everything was shut down.

So we drank a cup of coffee in the only place that was open and went for a little walk around town. Eventually, we found a good view of the local castle of Usell after we had only caught a brief faraway glimpse of it from the bus.

It was still a faraway view, but then we remembered: a distant view is often the best a castle has to offer.