Rocamadour in the Dordogne valley east of Bordeaux is one of France’s top visitor attractions, but unlike most of the other entries in tourism’s Top Of The Pops, it has been a hit for centuries.

Had visitor numbers been measured in the Middle Ages, Rocamadour would have topped such a statistic year after year, centuries before its competitors in today’s popularity contests were a twinkle in the eye of architectural history – 500 years before the construction of Versailles, nearly 1000 years before the Eiffel Tower first saw the light of day in the City of Lights.

Why Rocamadour is Top of the Pops for the Last Thousand Years

From the early Middle Ages deep into modernity, the sanctuary that has been carved into the Rocamadour stone was one of Europe’s prime pilgrimage sites, visited by crowned heads as well as ordinary folks. Most of the visitors came here in search of a cure for an ailment: in an age when medicine as we know it did not exist, a pilgrimage to a holy site often seemed the most promising option.

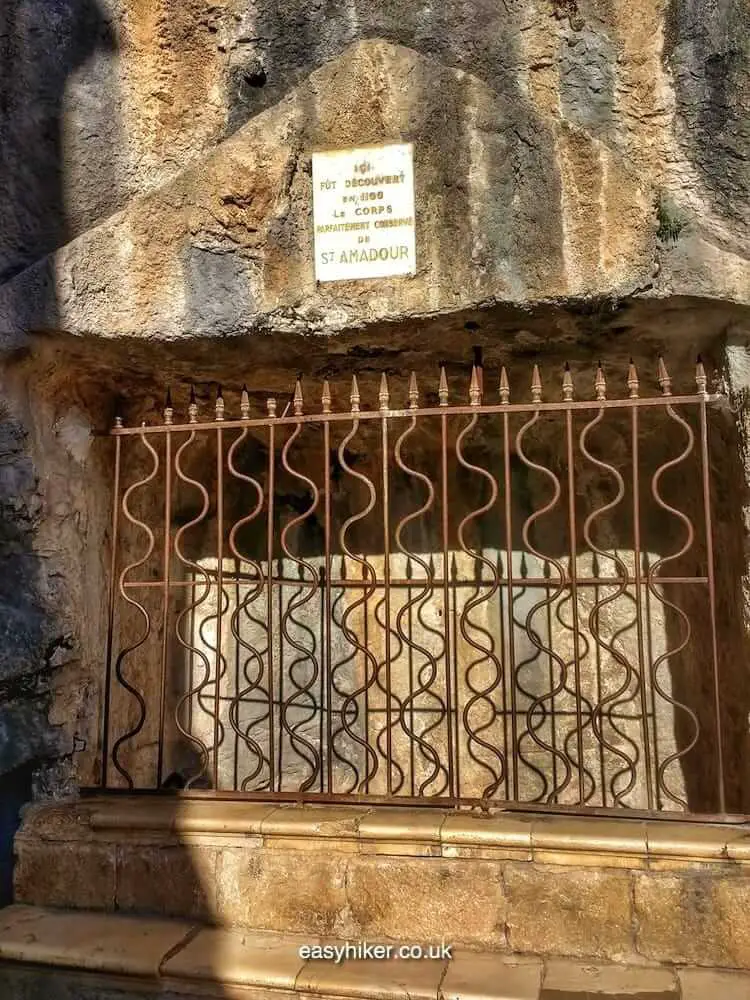

Rocamadour’s fame goes back to the discovery of a hermit’s undecomposed corpse that immediately turned to dust once it had been brought to a cemetery in the valley below. This was, the medieval mind concluded, clear evidence for the powers residing in the mountain – reports of which had apparently circulated since prehistoric times.

There are plenty of places where you can read about all that, the legend of the Black Virgin, the sword of Roland and the mysteries that swirl around the towers like the black predator birds of the Alzou Valley …

… so we are going to concentrate on something else today, offering you three brief but interesting walks that you can undertake in the sanctuary’s immediate vicinity.

And to reflect the special nature of Rocamadour, these walks embody a trinity of motives: one historic, one scenic, one spiritual.

Hospitalet in Rocamadour

For starters, we shall set out for a short journey to the village of Hospitalet, a little over 1 km to the east of the Sanctuary. In the Middle Ages, Hospitalet was where pilgrims could ease their pain and undergo treatment: not for the ailments they hoped their pilgrimage would remedy but for those they had contracted on their journey – broken bones, infected wounds, exhaustion.

Today, only ruins remain of what once must have been a very busy place.

Two routes are leading from the Sanctuary to Hospitalet: one is the Voie Sainte, the Holy Way, basically the uphill extension of Rocamadour’s medieval high street …

… the other the “high road” that starts at the top level of the Rocamadour complex in front of the castle. This is the slightly longer but also less physically challenging way, as it meanders slowly downhill.

There is, however, one thing that the two routes have in common: both offer magnificent views of the rock with the sanctuary and the chateau.

The Way of the Cross

The Rocamadour complex consists of three levels: at the bottom lies the Cité Medievale, the ancient high street, from which 261 steps lead up to the sanctuary with its series of shrines, and the whole thing is then topped by the castle.

Many visitors climb up the stairs from level 1 to level 2 but then either take the elevator up for the final stretch or waive this part of the complex altogether.

Which is a mistake, since they miss one of the rock’s most lovely parts, full of delightful twists and scenic views of the valley below.

Medieval pilgrims did not have any such option: this section was only developed in the 19th century. First came the modern castle (in 1841) and then, a few decades later, the way of the cross that leads up from the sanctuary.

It features 14 stations, the first 13 of which are little chapels with relief sculptures that commemorate Christ’s way to Mount Calvary.

Station no. 14, however, the Entombment, has been carved directly into the rock for the walk’s grand theatrical finale.

After this, you can stroll up one more flight of stairs up to the castle. You cannot visit the interior of the building but take a peek into its gardens from the ramparts which are the sole remains from the first chateau that was built here in the 14th century.

Alchemy

Most of you will probably not be aware that Rocamadour has a unique place in the ancient craft of alchemy. Most modern people associate alchemy with the attempt to turn ordinary materials into gold, but this was only one aspect of it.

Alchemy is better understood as a complete theory of universal change, transmutation and transcendence – any earthly benefits for humans, material (precious metals) or physical (medicine) were considered to constitute mere side effects.

Alchemy’s main concern was the transformation of energies. The energies of Rocamadour were accepted as a given (the evidence was held to be incontestable), so the first task of the alchemist was to locate them.

It was believed that the site’s energies were concentrated in St Michael’s Chapel that had been built underneath the place where Roland’s sword can be found stuck into the Rocamadour stone. (The legendary warrior Roland, mortally wounded at the battle of Roncevaux against infidel intruders, had requested the Archangel Michael to throw his equally legendary sword Durendal back into his native France, and this is where it eventually landed.)

Alchemists believe that St Michael’s Gate underneath and behind the richly decorated external walls of St Michael’s chapel is “the door that must be crossed”, a gate that leads the visitor into another world.

It is, however, not the only local source of mysterious energies. To find the gate’s complement, walk down the stairs into the Cité Medievale and turn right into Rue Coustoulau …

… continuing all the way to the bottom of the valley.

Cross the creek ahead of you and turn right into the forest. After a few hundred meters, you will arrive at a spring: the Berthiol Fountain.

See if you can spot any salamanders in the area: apparently, these yellow-spotted black lizards, a common symbol for fire in the Middle Ages, are (or at least once were) quite numerous here.

Actually, this is what first alerted the alchemists to the spring: the presence of these “fiery” animals seemed to point towards the reunification of the opposing forces of fire and water. Such a reconciliation of natural forces was understood as one key to the reunification of the human and the divine, man and God, the ultimate purpose of all serious alchemists.

All of this may all sound a little silly and surreal to the modern mind, but alchemy was a serious attempt to address what its practitioners thought was the root cause of man’s fundamental unhappiness in this world: his remoteness from God.

Modern projects to understand the fabric of reality are far less heroic – and may, one day a thousand years from now, be thought to have been just as silly. Who knows?

Finally, some practical tips. Of all the major tourist destinations we have ever visited, Rocamadour is easily the most difficult to reach by public transport. You can travel by train, but Rocamadour-Padirac station is approx. 4 km away from the village and not usefully serviced by any means of public transport. (A bus, line 876, comes every 4 hours.)

The country road between town and station does not make for a pleasant or even safe walk: there are neither sidewalks nor street lights. To get a ride, you must order a taxi in advance and be ready to pay the flat fare of € 35, a lot for such a short journey but you have no choice. (We were told that there were no commercial taxis in Rocamadour: all taxis are apparently under contract by the social services, and the available taxis need to come in from the surrounding small towns and villages.)

But all this additional trouble and expense will be richly rewarded by the magic of Rocamadour. It is a unique place, whether or not you can find relief from the arthritis in your toes – or find yourself transformed by the mountain’s energy on some deeper level of your soul.