Just as any trip to Tuscany feels strangely incomplete without the glories of her capital city, no visitor of Florence should leave without having made an excursion into the surrounding countryside, no matter how brief.

Tuscany is one of the world’s truly legendary landscapes, a category which includes places like the Provence and the Black Forest.

Everybody, including people who have never been there, has an idea of what they look like – which is just another way of saying that we have all seen the same picture postcards.

To tell you the truth, having lived for seven years in a region known as “Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur”, I am yet to see a purple lavender field, and I assure you from my own experience that the Black Forest is not black (and that only very few Black Forest women string apples and oranges to their hats).

And so it is with Tuscany. Greenish-yellow hillscapes that are punctuated by the stark shadows of cypress trees in the afternoon sun: this is what you can see in certain spots of southern Chianti approaching Siena.

Around Florence, the climate is harsher, colder and wetter, and you are more likely to see oakwoods as well as fields of grain and vegetables (the Arno valley is one of the agriculturally richest in all of Italy: this was the original source of Florence’s wealth).

Nevertheless, and despite a good deal of urban sprawl …

… there are several interesting day trips on offer.

We picked a route that allowed us to follow in the footsteps of the original Renaissance Man – as well as his flight path. Incidentally, we also found out about the physical origins of the cloth out of which the city’s urban fabric was woven.

In search of the magnificent Renaissance Men in their Flying Machine in Fiesole Florence

If you want to follow us, take bus no. 7 from the Piazza Adua stop opposite Santa Maria Novella station to Fiesole (frequency: every 15 to 20 minutes) …

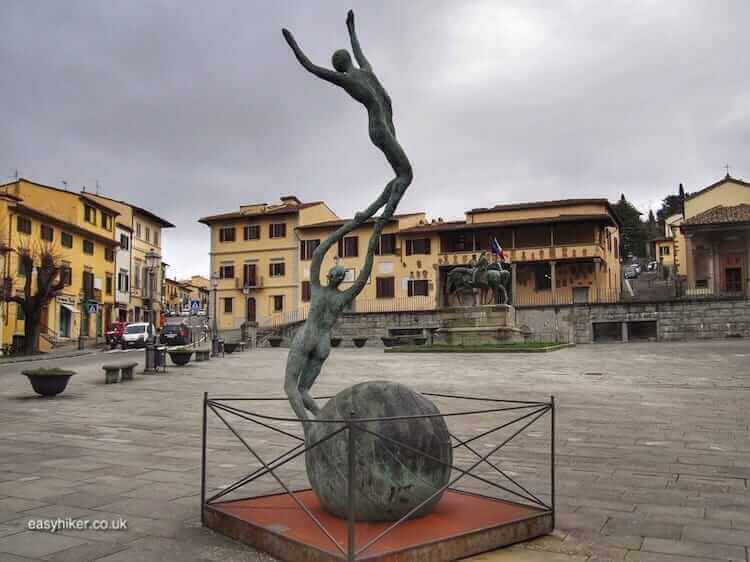

… and from there (the final stop) the footpath on the right hand side of the market square …

… to follow the signs that lead you in the direction of Monte Ceceri.

Right at the entrance to the nature reserve, you will find an information panel: take a photo of its map on your smart phone. The recommended walk around the reserve is a simple loop, but there are also other paths with different numbers, and it can get a little confusing if you spot one of those signs along the way.

You will not want to miss any of the sites nor spend hours looking for the exit after you have seen everything. With a photo, the trail system is easy to manoeuvre.

Believe me: the Easy Hikers are experts in losing their way – rare is the hike where we do not do so at least once – but on Monte Ceceri, we managed perfectly well.

The top billing on the list of attractions belongs to Monte Ceceri itself, the launching pad for the world’s first flying machine.

Flying was Leonardo da Vinci’s great obsession. After his death, people found hundreds, some say thousands of designs for flying machines that he had stashed away in drawers and folders.

The only design of a flying machine in Fiesole Florence that ever “took off”, however, was the ornithopter, meant to fly by flapping its wings, which Leonardo completed in 1505.

Leonardo may well have been the world’s first mad scientist, but he was certainly not mad enough to drive the machine himself. Instead, he decided to bestow the honour of “filling the universe with wonder” (Leonardo’s own words) on Tommaso Masini, also known as Zoroastro da Peretola, a dedicated member of Leonardo’s large entourage of young male assistants.

One morning in 1505, the two went to Monte Ceceri to write aviation history – but for a reconstruction of what exactly happened, we only have Leonardo’s words to rely on.

Masini took off, Leonardo later reported, but soon entered a tailspin and eventually came to a crash landing after a flight of about 1000 metres, breaking a leg and several ribs. For Masini, a trip to the hospital followed – and for his master, a trip back to the drawing board.

Whatever you may think about this episode, you got to admire Masini’s guts for leaping off that cliff, which was much barer then than it is now, with no trees around to soften his landing (the forestation is a product of the last 80 years).

Walking down the hill – in truth, it is not much of a Monte – and around the bend at its foot, you will discover the second link of this forest to the history of Florence.

For centuries, the mountain was used as a quarry …

… that provided the architects of Renaissance and Baroque Florence with stones for their buildings.

Several information panels at the sites explain and illustrate the historical background, but there are also reconstructions of stonecutting tools and some remnants of the working men’s facilities.

Two old quarries have been preserved: the Cava Sarti just underneath Leonardo’s launching pad and the Cava dei Braschi a little further away – this may be the right time to remember that cava is the Italian word not for a cave but for a quarry (a cave is a grotta), although in this case, the distinction is almost irrelevant.

The Cava dei Braschi is located on a sidetrack of the loop, which you will need to finish first before, at the fork, follow the path that is identified by a different set of markers.

This may sound more complicated than it actually is. In fact, it is fairly self-evident if you have taken a photo of the map. Remember what we told you?

Overall, the Monte Ceceri walk is a fascinating trip into history with frequent reminders of the mountain’s past as a source for building materials …

… and its place in the history of aviation …

… while it also provides great scenery …

… and beautiful motives.

It is a perfect escape from the hustle and bustle of Florence.

From the Cava dei Braschi, take the short walk to the bus stop Regresso: the walk ends where Leonardo’s flight did – Masini is said to have landed in the exact space opposite the bus stop where the road bends. It took Masini a few weeks to recover, apparently, but you will be back in Florence from here within 30 minutes.