There are two ways of exploring Naples. You can opt to tick off the well-known points of interest: the Caravaggios and the catacombs, the churches and the royal palaces.

But you can also venture out into the streets of the city without a fixed itinerary in order to experience Naples on a visceral level: immersing yourself in the spectacle – the noise, the smells, the colours – in search of the city’s soul rather than its sights.

The statuettes and images that you can spot on nearly every wall and building in town are as much part of this spectacle as noisy scooters and clotheslines that span entire streets.

Neapolitans, it seems, do not much care for living any part of their lives in the abstract: more even than the people in other Catholic cities of Italy, they appear to need visible manifestations of what they believe in.

Which is why the city has always been full of shrines dedicated to blessed virgins, baby Jesuses and assorted saints, and also why it has always reserved sacred spaces for its local heroes.

Chief among those used to be Totò, a Naples-born comedian who was Italy’s most popular performer in the 1950s and 60s. But his memory is fading as are the murals on Via Portacarrese, once a famous tourist attraction.

These days, you can roam past these murals in blessed solitude down a nearly empty street.

Totò – together with Sophia Loren and Padre Pio – has lost his place in the hearts of the Neapolitans to someone else. The evidence for this is on display everywhere in the streets of the city.

Maradona – The D10S of Naples

First, a look at the bare facts. Diego Maradona was the world’s best football player in the early 1980s, and when he left Barcelona in 1984, he could have chosen to go to any of the biggest, richest and most storied clubs in the world.

Instead, he came to Napoli, a team that had barely escaped relegation from Italy’s top division the previous season and had never won a national championship. With Maradona, that was about to change.

A third place in his first year was followed by a championship (they also won the cup in the same season, only the third team in the league’s history to complete the “double”) and, after that, by another title. During Maradona’s six-year-spell, Napoli also won its only European trophy ever, the UEFA Cup of 1989.

This, however, is clearly not the full story. Wayne Gretzky and Michael Jordan helped their teams to win a string of championships at roughly the same time, and while the people in in their adopted home towns have fond memories of their former star players, nobody in their right mind over there would draw parallels between Gretzky’s or Jordan’s athletic careers and the life of Christ.

Naples, however, is not Edmonton. For one, Neapolitans feel very strongly that the Italians from the North look down with contempt on their crumbling and impoverished city. As a defense mechanism, they have adopted a mixture of cheeky defiance and chutzpah: the mentality of the underdog who is defending what is left of his pride and dignity against overwhelming odds. In Diego Maradona, they recognized a kindred spirit.

Maradona was a child of the slums in his native Buenos Aires, and although success took him out of the favelas, it could not take the favelas out of him. A street kid was what he remained all his life, displaying – on a good day – the cunning and cheek of an Artful Dodger, like when he scored his most famous goal by using his arm to steer the ball across the line (“a little with the head of Diego Maradona, a little with the hand of God”, as he later explained).

But he could be more than a little naughty, too, and certainly was not one to turn the other cheek when under attack. Bombarded with racist insults from opposing players and fans throughout the Spanish Cup final of 1984, he waited until the final whistle to take out three members of the opposing club: one with a head-butt, the second with a swing of his elbow and the third with a well-aimed kick. (A mass brawl ensued in front of 100,000 spectators which included King Juan Carlos, and Maradona was told to leave Barcelona.)

Maradona – the D10S of Naples played and lived by his own rules – and died that way, too, after a turbulent private life full of well-publicized scandals. In the eyes of Neapolitans, however, personal pain and misery only added to his legend.

And this legend is alive as ever. Nearly every bar and bistro in town conjures up Maradona’s presence: places where workers go in the middle of the day for a quick coffee and a smoke …

… as well as fancy joints where middle class folks enjoy their pre-dinner drinks.

Private homes proudly display their loyalty …

… which businesses of all kinds then try to turn into profit – including companies that you would not readily associate with football, such as, yes, funeral parlours.

On open squares and intersections, monumental images are dedicated to the city’s adopted son …

… while in quiet side streets, you can find more intimate declarations of private devotion.

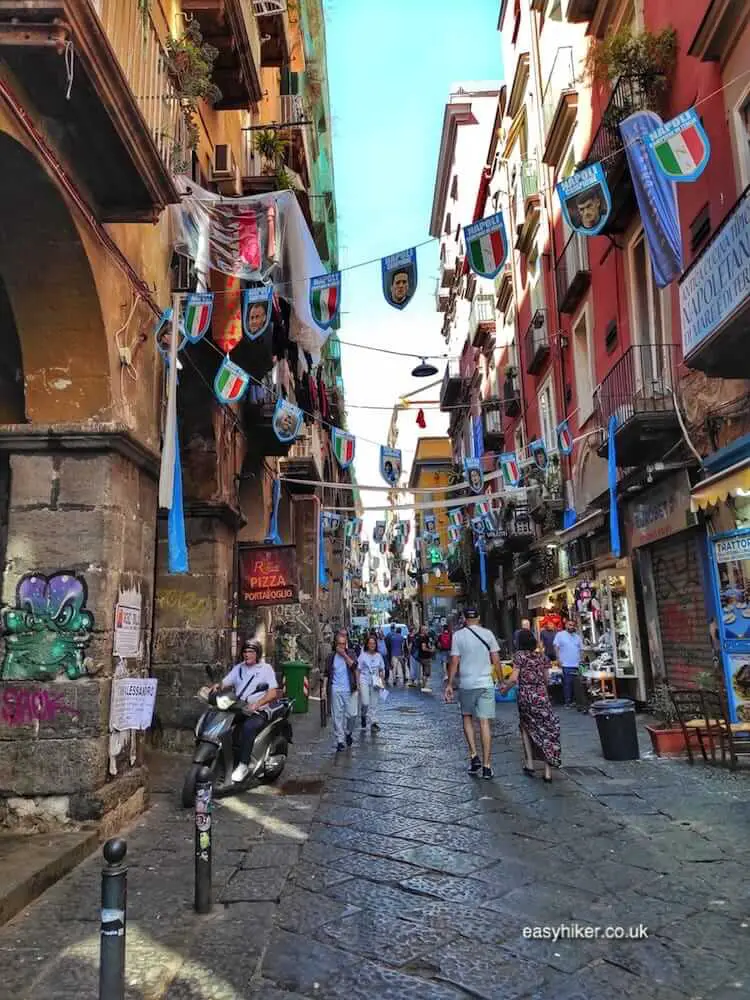

It is the infinite variety of portrait styles and designs that makes Maradona spotting such great fun. Focus primarily on the three parallel high streets of the Centro Storico (the decumani with the Via dei Tribunali in their middle) and the narrow lanes that intersect and join them, but you can also strike lucky in fancier areas around the Piazza del Plebiscito.

But wherever you go, you should finish your tour in the centre of the cult: the city’s noisiest and most anarchic district, the Quartieri Spagnoli.

It is here – on Via Emanuele del Deo – where the Great Outdoor Shrine of the Maradona cult has sprouted. This is what the place looked like a few years ago (I got the photo from the Internet) …

… and this is what it looks like today.

Within a few years, an amateurishly decorated backyard where, perhaps, a few faithful would gather to exchange memories about their football club’s most successful spell has mutated into a veritable pilgrimage site: the Lourdes of Naples.

It is true that the overtly religious references of the Maradona cult may raise an eyebrow or two …

… but there is another way of looking at it.

Over the years, the story of Diego Maradona has taught the Neapolitans that the world, no matter how rigged it may be, is not rigged to an extent where a kid from the slums cannot succeed on his own terms, without needing to betray his inner self and to cozy up to the rich and powerful.

Indisputably, this has helped thousands of people to build up the inner strength which is required to survive in a rough and hostile environment. Maradona has given these people hope, and is that not one of religion’s most sacred and noble purposes?

“You have given your life so thousands could live theirs in pride and dignity.” That’s what the inscription under one of the uncounted Maradona portraits in town says, and that is how the people of Naples appear to think of Maradona.

Whatever you may think of the life the man led and the choices he made, that is no small achievement – and ultimately worth more than all the trophies he won on the football field.