… whether you are interested in the history of landscaping or not

… parks and public gardens reflect the times in which they were created no less than buildings do, because tastes in landscaping vary as much as architectural ones.

In theory, it may be possible to adapt a landscaped garden to a newly emerging fashion; this would certainly be much easier and much less costly than doing the same with an architectural structure.

But in actual fact, parks quite often manage to preserve their period charm.

The formal gardens of Versailles, for example, illustrate the tastes of “absolutist” France at least as vividly as the building to which they are attached

The parks of Chiswick House remain a prime example for the fashions of classicist Britain – as instructive as Regent’s Park is for those who want to experience the flavour of a later version of London.

But what about modernism? There is practically no major town or city in the western world which has totally escaped its impact, but modernism’s influence on landscaping fashions has been altogether less obvious – and more benign, too.

The central tenets of modernism – straight lines, uncluttered design, and a somewhat patronizing form of socialism – have done less damage to our cultured landscapes than to our cities.

Probably for the reason that the creators of the 1960s council homes never expected to live in one of the flats they designed, whereas they would certainly have imagined taking their kids to the public parks they were about to build.

More than other countries in Europe, Germany is full of 1960s parks, simply because most German cities had to be totally redesigned in the aftermath of WWII.

Grugapark in Essen

The (1 hour north of Cologne) is one of the largest, grandest and most representative post-war parks in Germany. Its roots, however, reach further back to the early decades of the 20th century.

The first plans to build a large park for workers and their families in Essen, an industrial town which is mainly famous as the HQ of the Krupp company, date back to the early 1900s.

It was only in 1929, however, that the Great Gardening Exhibition of the Ruhr Area (the German acronym for which is GRUGA) gave the city what it had craved for so long. The exhibition was a great success, something that was not lost on the Nazis when they came to power a few years later. They chose the Grugapark as the venue for their second Reichsgartenschau (National Gardening Exhibition) in 1938.

This probably did not help the Grugapark in Essen in WWII: the site – unusually for a public park – was targeted in an air raid as late as March 1945 and completely destroyed.

Reconstruction followed gradually after WWII, but most of today’s park was laid out for another National Gardening Exhibition, the Bundesgartenschau of newly prosperous and democratic West Germany in 1965.

The park reflects the will to combine two different objectives: firstly, to give the working people of Essen what they wanted – entertainment (a bandstand for music shows), places where the children could roller skate, swim or play ball (concentrated in the western half of the area), and many places where families could simply sit down on the lawn and have a picnic …

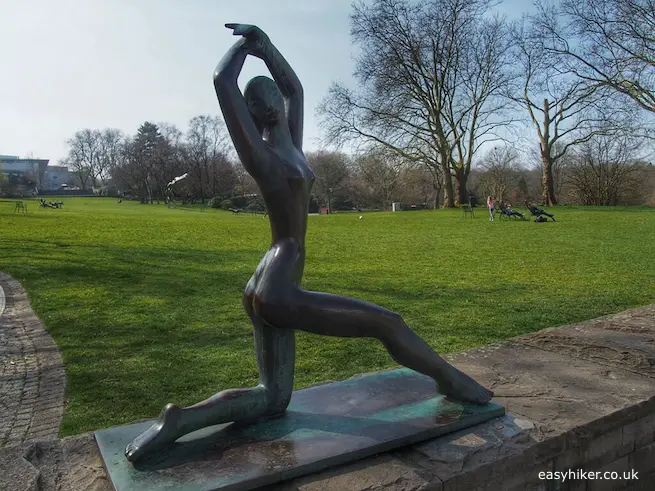

… but also, secondly, to educate and to civilize the working class: to bring culture to workers by familiarizing them with science (botanical gardens) and art (many of the park’s sculptures were made by famous artists).

The idea of pacifying the working classes by piping a mix of professional sports and reality shows into their homes would follow later – in the 1960s, everybody still believed in “social progress”.

The architects of the modern Grugapark in Essen certainly made sure that the new public garden would have many attractive features: the so-called “alpinarium”, an artificial alpine landscape, …

… a lake …

… and greenhouses are all part of the park’s original “furniture”…

… while the Ronald McDonald House – constructed by the McDonald’s charity to accommodate the families of children who are treated in the city’s near-by pediatric hospital – was added later. The building was designed by the eccentric Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser.

Most importantly, the Grugapark in Essen is a great “little escape” if you have a couple of hours to kill in Germany’s industrial heartland – whether you are interested in the history of landscaping or not.

To get to the Grugapark in Essen, take subway line U11 and get off at Messe Gruga station. Please note, entrance fee for adults: €4.

Marcia, Ronald McDonald houses are usually found near hospitals for children. These houses provide the facilities that enable families to be near their sick children.

Looks like there’s something for everyone here – even a Ronald McDonald House. Didn’t expect to see that at all.