The Centro with the Madrid dos Austrias, the Gran Via neighbourhood, Malasana and Chueca: last week, we gave you a good roundup of the Spanish capital’s “greatest hits” while walking through its central districts.

But big cities like Madrid are always a sum of all their parts, not only the three of four that make up the urban core.

Greatest Hits Side B of Madrid

Which is why today we will familiarize ourselves with the other residential quarters in the town centre – and, yes, some of the outer-lying districts as well. Together, they make up a fascinating mix of the posh and the popular, the storied and the colourful.

We start with the most storied of them all, the Barrio de las Letras.

The reason why this quarter has so many stories to tell is quite simple: it had so many years to accumulate them. Because this is where, in the early days of royal Madrid, everybody who wanted to cash in on the presence of the newly established court – adventurers and skilled artisans but also writers and artists – came to settle, simply because there was nowhere else to go.

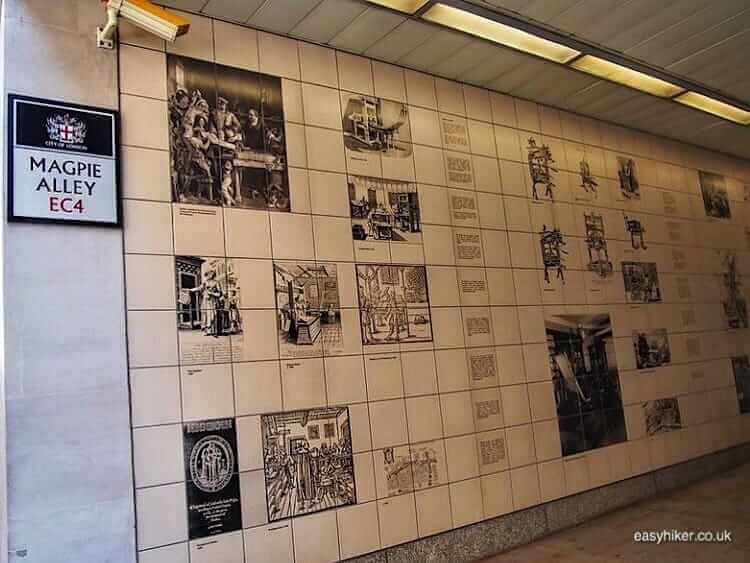

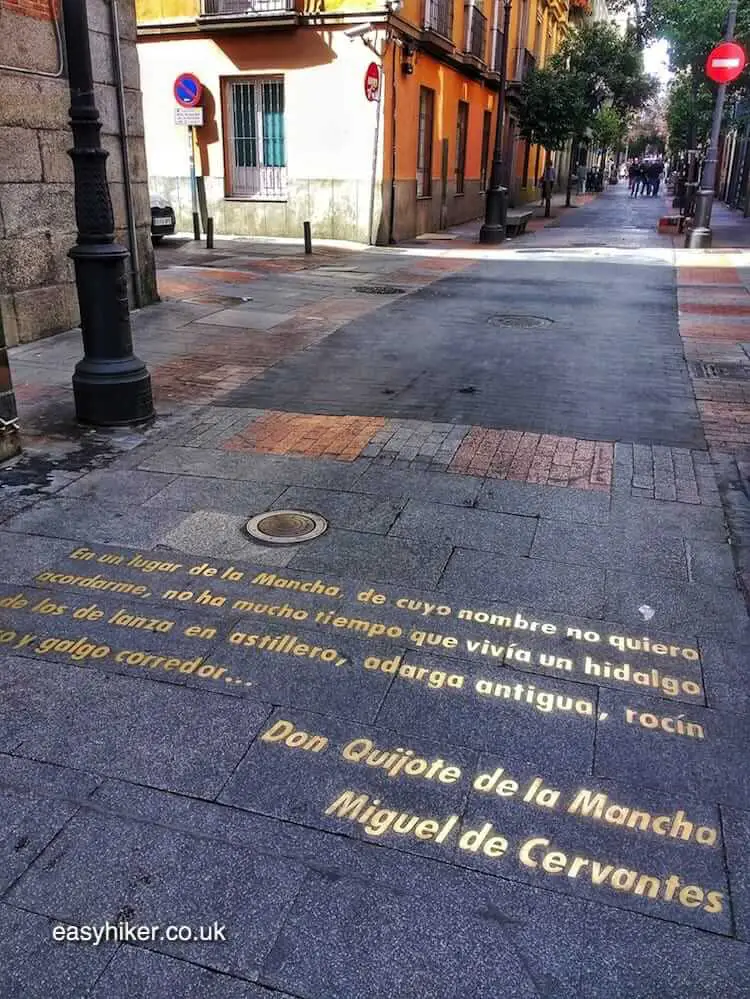

Today, people who stroll down the Calle de las Huertas and its neighbouring streets in the Barrio’s centre are reminded of the area’s literary past wherever they step.

The Letras was also the part of town where Miguel de Cervantes, the author of Spain’s most famous work of literature, spent nearly all of his life. Only one of his many residences, however, can be identified with certainty: that is the house where he died, located on the corner of Calle de Leon and Calle Francos.

In 1833, the man who had come to own the building – which was apparently in a very poor state – applied for a permit to have it torn down, when, at the last minute, King Ferdinand intervened with a request to delay the building’s destruction until his government had raised the funds to buy the house and turn it into a museum.

The owner, undoubtedly flattered by the royal interest in his commercial dealings, weighed up the royal request – and then, after careful consideration of all aspects, had the building torn down anyway (my favourite among all the stories about the Barrio), so the memorial plaques that you can see today on 2 Calle Cervantes actually decorate a fairly recent construction.

Incidentally, the old residence of Lope de Vega, the other key figure in the Golden Age of Spanish Literature, still stands a few houses further down on Calle Cervantes and has been preserved rather well …

… but all the same, few people want to take photos of it. After all: everybody knows Don Quijote, but who has ever heard of Lope’s The Sheep Well, apparently the biggest hit on the stage of Spain’s Golden Century?

Modern times have not been very kind to Lope – and did not even spare him the posthumous indignity of having his old home street named after his bitter rival. (He and Cervantes did not get on well, by all accounts.)

The literary traditions of the Barrio de las Letras were continued in the 20th century by Madrid’s most famous occasional resident, Ernest Hemingway, who often came to the restaurant El Sobrino de Botin on 17 Calle de Cuchilleros: to eat, to drink, but often also just to write, occasionally from early in the morning until dinner time on a table that the owner – who was also Hemingway’s friend – had set out for him on the restaurant’s less busy top floor.

Perhaps as a little thank you, Hemingway went on to use Botin’s as the location for the final scene in his debut novel The Sun Also Rises. The star-crossed lovers, Jake and his former girlfriend Brett, have a meal together, board a taxi and – we are left to assume – part forever.

“We lunched upstairs at Botins. It is one of the best restaurants in the world. … Brett did not eat much. She never ate much. I ate a very big meal and drank three bottles of rioja alta.”

Which is a lot of booze, even for a Hemingway character. Jake appeared to enjoy a tipple no less than Don Ernesto himself and would surely have appreciated the neighbouring barrio of La Latina, the longest and most picturesque drinking counter of the Spanish capital.

Built on the site of a medieval Islamic fort, La Latina is today centered on two parallel high streets – the Calle de la Cava Baja and the Calle de la Cava Alta – that are lined by taverns and cantinas.

The best time to study and admire the often quite beautiful interiors of the barrio’s watering holes is the afternoon …

… because after dusk, they fill up quickly with noise, laughter and shuffling feet. If Madrid is a city that never sleeps, La Latina is the place where it stays awake during the wee hours.

On its eastern side, beyond the Calle de Toledo, the Barrio shades into Lavapies, which is as lively and colourful albeit in a different way and on a different schedule.

Lavapies has always been the quarter for people who have to work hard for a living, and in recent times, it became the hub for immigrants from all over the world.

It is also the place where best to study the corralas, Madrid’s characteristic tenement halls whose “walkways in the sky” are arranged around an interior courtyard.

You can see a typical example of this type of building at the corner of Tribulete and Mesón de Paredes.

At the eastern corner of Lavapies, the Paseo del Prado begins, the gateway to an entirely different world. Salamanca to the north of the Retiro park is the most expensive neighbourhood in Madrid.

At its heart, three streets run parallel to each other, of which the Calle de Lagasca in the east is the most quiet, a sequence of handsome apartment buildings that is occasionally accentuated by a private clinic or a gourmet coffee bar.

Calle de Coello in the middle of the three streets is a little livelier: equally leafy and lined by similarly handsome residential buildings, it features more – generally quite fancy – shops, many of which offer fashion brands that may be interestingly unfamiliar to non-Spaniards (Silvia Navarro, Meermin).

By contrast, Calle Serrano and Calle Ortega y Gasset which mark, respectively, the western and northern borders of central Salamanca, are both multiple-lane highways and lined by outlets of the world’s top designer names.

The southern border of Salamanca is established by the Retiro, Madrid’s most famous public garden, …

… which has also given its name to the district around it, although this district consists of little more than a thin layer of hotels, government buildings and museums.

If you are looking for a park, we suggest the Casa de Campo in the west of the Royal Palace. (We had a post on that once from a previous visit, but it got lost in cyberspace when we converted our website into a different format.)

More interesting even is a trip to one of Madrid’s outer quarters. Okay: these suburbs may frequently come across as a little grim, and if central Madrid does not do pretty (as we said last week), outer Madrid is even more dismissive of the idea.

Still, these districts, too, are elements in the sum that makes up the city. We suggest a trip to Tetuan in the north, located on the urban fringe of the capital, which is also the home of the largest indoor market in Spain and, incidentally, all of Europe.

The Mercado de Maravillas on Calle de Bravo Murillo (Metro station: Quatro Caminos) features more than 200 stalls with fruits and veg from all over the world as well as a wide range of small restaurants and tapas bars.

Alternatively (or additionally), you can also accompany us on a walk through the outer-lying district of Arganzuela for an exploration of the city’s newest visitor attraction.

More of that next week!