Themed Walks in Paris

The Bastille Day Walk

What better way to celebrate the 14th of July, the French national holiday, than to trace its events, following – as literally as that is technically possible – in the footsteps of history in one of our themed walks in Paris?

Whatever you may think of the French Revolution, at least, Bastille Day is one national holiday that does not commemorate a bunch of stuffy middle-aged guys congregating in their Sunday best to sign some document or the other, but a REAL REVOLUTION, one with blood on the pavement and – as you shall see – heads being carried through the streets on pikes. (This is probably the right point to advise our faint-hearted guests to go away and read something else.)

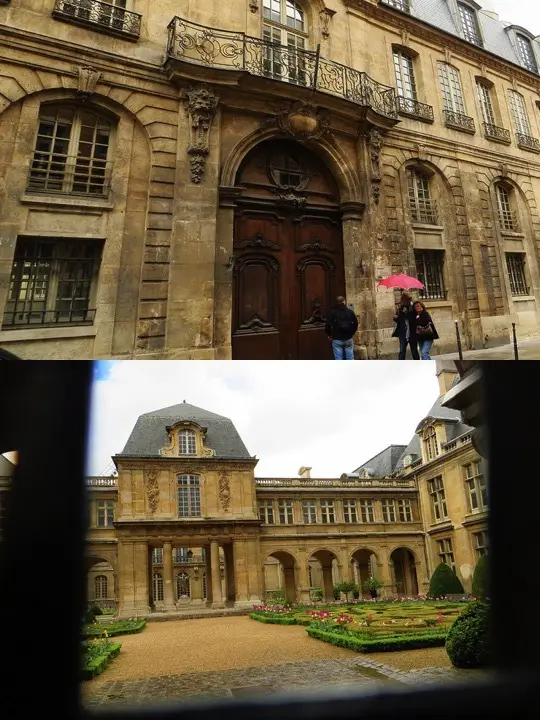

For one of our themed walks in Paris, with this one we start our walk with a stroll through the Marais – down Rue Rambuteau and Rue des Francs Bourgeois, Metro Rambuteau – for a taste of pre-revolutionary Paris.

Old mansions with arched stone entrances and interior courtyards that are big enough for horse-drawn carriages to manoeuvre around exist in other parts of Paris, too, but only here does their number create the critical mass which is required for the delivery of an atmosphere.

If you concentrate hard enough, you even think you can hear the wheels on the cobblestones and the high-pitched laughter of women in vertiginous wigs, perhaps even smell the stench of their perfume.

Next, we move to the other side of the Place de la Bastille, into the Faubourg Saint Antoine. Then and now, this has been the centre of the Parisian furniture-making trade – and a hotbed of all French revolutions from the 18th and 19th centuries, the area where many of the hardcore republicans came from.

It is important to bear in mind that these carpenters and furniture makers were not members of an industrial working class, but proud artisans who would have seen themselves as members of the Third Estate, not as an urban lumpen proletariat.

Still, one cannot help thinking that the close proximity between the luxury of the Marais and the relative poverty of the neighbouring Saint Antoine did not exactly help to relieve tensions.

The Bastille itself was a medieval fortress that covered virtually the entire area of today’s Place de la Bastille. (The fortress has since been destroyed. A few stones were moved to the corner of Boulevard Henri IV and Quai des Celestins, and the layout of the outer walls is outlined on the platforms of Bastille subway station.)

Everybody knows that in July 1789, the Bastille – used at the time mainly as a somewhat genteel prison – was practically empty. (Not least because the Government had cleared it out in the preceding weeks, obviously smelling trouble in the air. One of the last to go was the Marquis de Sade, shipped off to a lunatic asylum after he had attempted to incite people in the street by shouting at them from his cell that “They are massacring the prisoners inside! You must come to free them!”).

For some reason, I had always taken the seemingly logical next step and assumed that there was no real fight over the Bastille on that day – after all, who would defend such a largely symbolic structure? It turns out that I was totally wrong.

This was the situation on the morning of July 14: France was gripped by a political and economic crisis, the King who had initially promised reforms had changed his mind and opted instead to have Paris surrounded by loyal troops. Many in the Parisian population felt that they had little choice but to arm and defend themselves.

On July 13, revolutionaries had taken weapons from the Arsenal but there had been no ammunition, and everyone knew that large amounts of gunpowder had recently been shipped to the Bastille – where they were defended by 82 so-called “veteran soldiers” (army men who had been given seemingly cushy jobs, being too old to fight in battle) and a reinforcement of 32 Swiss mercenaries, who were part of a much larger contingent that was deployed on the outskirts of Paris (near today’s Eiffel Tower).

De Launay, described as “badly beaten”, shouted “Enough! Just let me die!”

Gathering in the streets on the morning of 14 July were about 1000 militants who were getting increasingly restless and angry as the day went on – until the Marquis de Launay, the commanding officer of the Bastille, saw no alternative but to invite them in to discuss matters, still, however, refusing to surrender.

In order to appease them, and as a sign of goodwill, he told them that he would not have his men shoot at the crowd under any circumstances, showing them that his cannons were not even loaded.

Word of this spread quickly as soon as the negotiators returned to the militants’ camp, and some of the more daring revolutionaries climbed over the Bastille’s wall into the courtyard to lower a drawbridge. Hundreds of militants quickly stormed in, the soldiers were told to retreat to the towers, and when the mob tried to lower a second drawbridge, they started to shoot down into the crowd, killing 98 attackers.

The mob withdrew, but it quickly became clear that the situation was untenable for the defenders, and eventually the Marquis de Launay had to surrender. The mob lynched a few of the defending soldiers, let most of the Swiss run away and took de Launay as a prisoner, dragging him towards the town centre, together with his three officers, down – what are today – Rue Saint Antoine and Rue Rivoli.

If you found the story so far not particularly heroic and perhaps even a trifle disappointing, having expected a bare-breasted Marianne to give the come-hither to the revolutionary menfolk on the barricades, I can only tell you that you ain’t heard nothing yet – it gets a lot worse.

The mob proceeded to City Hall ….

…where the unpopular mayor, Jacques de Flesselle, was also taken prisoner. Outside the building, a discussion about the fate of the prisoners began, with a “People’s Trial” at the Palais Royal emerging as the preferred option.

De Launay, whose state at this stage of the events is generally described as “badly beaten”, shouted “Enough! Just let me die!” and is reported to have kicked a pastry cook named Dulait – you gotta love that level of detail – in the groin. In the ensuing scuffle, he was stabbed repeatedly and bled to death.

His head was then sawn off and fixed on a pike to be carried through the streets. His three officers were also killed. Somewhere along the way to the Palais Royal, accounts differ as to the exact whereabouts, the single surviving prisoner, the Mayor of Paris, was also “lost”, setting the tone for all “People’s Trials” of the coming centuries.

(Today’s Hotel de Ville was built in the Belle Epoque – works were completed in 1892 – but is a close copy of the 16th century Renaissance building that stood here in 1789. The original was destroyed in 1871 when, having served as the HQ of the Paris Commune, it was set on fire by another generation of Parisian revolutionaries as anti-Commune troops approached to finish off the uprising.

Today’s building was constructed inside the remaining stone shell. The original City Hall played another important role in the eventual denouement of the Revolution: it was here where, on 27 July 1794, Maximilien Robespierre – the original “Mad Max” – was shot in the jaw and arrested with his followers, an event that ended their “Reign of Terror”.)

We follow the mob on its way to the Palais Royal, which had been chosen as the “logical” destination of the revolutionary procession not so much because it would have been so menacingly near to the Royal Palace – the King resided at Versailles – but because it was, at the time, very much the “people’s square”: not at all the island of urban tranquility that it is today but a lively city square, full of groups in heated discussions, coffee houses and the occasional brothel.

It was here where, on the evening of July 13, Camille Desmoulins held a legendarily inflammatory “aux armes citoyens” speech at the Cafe Foy, 57-60 Galerie Montpensier, now a branch of the Marc Jacobs chain of shops immediately to the left of this view.

After the crowd’s arrival at the Palais Royal, accounts get a bit blurry as to what happened next. Presumably, they held a big party, the mother of all the 14th of July parties that are still celebrated all over France. Plans to march to Versailles – a good ten miles – to have a word with the King were, at any rate, quickly dropped.

That gives us the freedom to look at other places of revolutionary interest near-by – with the Place de la Concorde at the top of the list. This is where the revolution’s most famous accessory stood, the guillotine. It was erected near the Hotel Crillon, in the place where the statue representing the town of Brest is standing today.

Like thousands of others, King Louis XVI (“Citoyen Capet”) and Queen Marie Antoinette were also executed here, in January and October 1793 respectively. One would have thought that those two executions marked the end of the revolutionary bloodshed – but, in many ways, this was only the beginning. 96 percent of all the Revolution’s victims died after October 1793.

Many of the Revolution’s key events are connected to buildings that no longer exist. From the Place de la Concorde, walk into Tuileries Gardens whose entire width, across what is now the Avenue du General Lemonnier …

… was once covered by the Tuileries Palace . The Arc de Triomphe de Carousel (which still stands) marked the ceremonial entrance on the palace’s far side.

The palace was stormed by a mob on 10 August 1792. Nearly all the servants and guards were killed while the royal family itself was taken prisoner.

On the left hand side of Tuileries Gardens, facing Rue Rivoli, you would once have found the Salle du Manege – this was the place where the revolutionary Parliament debated, the new constitution was drafted and the process against Louis XVI unfolded.

The Tuileries Palace was willfully destroyed – partly set on fire, partly blown up with explosives – in the last days of the Paris Commune to “rid the Parisian cityscape of its last vestige of royalty”. The Salle du Manege was razed in 1802 to make way for today’s Rue Rivoli.

Turn northwards from Rue Rivoli into Rue du 19 Juillet for a couple of blocks until you arrive at the Place du Marché-Saint-Honoré. This was where the Jacobin Club once had its offices, originally a group of progressive deputies that quickly became the driving force behind much of the later stages of the Revolution.

They met here in the refectory of an old Dominican monastery – the French called Dominican friars “Jacobins”, due to their long association with the Rue St Jacques. The modern square, however, fails to exude much of an ancient atmosphere, the Jacobin Club having been destroyed after the fall of Robespierre in 1794.

For that type of atmosphere, we have to go further afield.

Of all the streets in Paris, the Rue du Commerce Saint Andre (Metro Odeon) is the one that provides the most “authentic” flavour of a late 18th century neighbourhood. It originally extended beyond the Boulevard Saint Germain, but while that bit has since been razed (the statue of Danton more or less marks the place where his house once stood), the northern end of the street has been pretty well preserved.

This is where Marat published his hate sheet L’Ami du Peuple (at no. 8), and the walls of the Café Procope right opposite – est. in 1688 – must have heard quite a few people “sing /singing the songs of angry men”.