Scenic landscapes and a historical monument on the beach promenade of Rügen, Germany’s largest island

It may be a truth universally acknowledged (at least across that section of the universe where English is spoken) that Binz Means Heinz.

In modern Germany, Binz means beach

It has always stood for sandy beaches and seaside fun – at least since Binz became one of the busiest and most popular holiday resorts on the country’s Baltic coast.

Binz – located on the far side of Rügen, Germany’s largest island – possesses one of the longest, widest and most scenic beaches of Northern Europe, which stretches for miles along the bay of Prora.

It is a pity that this beautiful landscape is almost unknown outside of Germany. Very few foreign visitors ever come here.

On the other hand, this benign neglect has allowed the bay of Prora – and, more generally, the entire island of Rügen – to preserve a very specific German charm: the reason, after all, why the beach looks so Teutonic is not only that it is straight as a die, almost as though an engineer had drawn a line to separate the land from the sea, but also that the wicker beach chairs give it an almost suburban neatness and orderly appearance …

… and that the inevitable nudist beach (“FKK” in German, so don’t say you have not been warned) is not hidden behind a high fence – separated neither from the other beaches nor from the trail – and that nothing therefore protects the “beach promenade hiker” from catching sight of a few dangly bits here and there.

To our surprise, German nudists even appear to allow fully clothed folks on their beach, so it seems that they are more relaxed about these things in Germany than in, say, Britain or France, where no-textile beaches are generally hidden away and fenced off, as if to isolate a dangerous virus.

The beach promenade extends northward for approx. 10 km all the way to the Sassnitz ferry harbour. The coast will be on your right hand side throughout, …

… and about 100 metres on your left, behind the trees, you can find a road where you may catch a bus (line S 20, roughly every 30 minutes) to either Binz or Sassnitz whenever you want to end the walk.

Along the beach promenade, you will find a good deal of evidence for Binz’s past as a smart and highly fashionable resort. After all, when seaside holidays became fashionable in the late 19th century, the nearest major population centre or “industrial” town was about a day’s journey away (with the means of transport then available), so a certain level of exclusivity was part of Binz’s attraction.

On top of that, the long coast provided enough space for large villas with large gardens – after all, the members of the wealthy bourgeoisie had not driven their money to work so hard for them in order to live in beach huts.

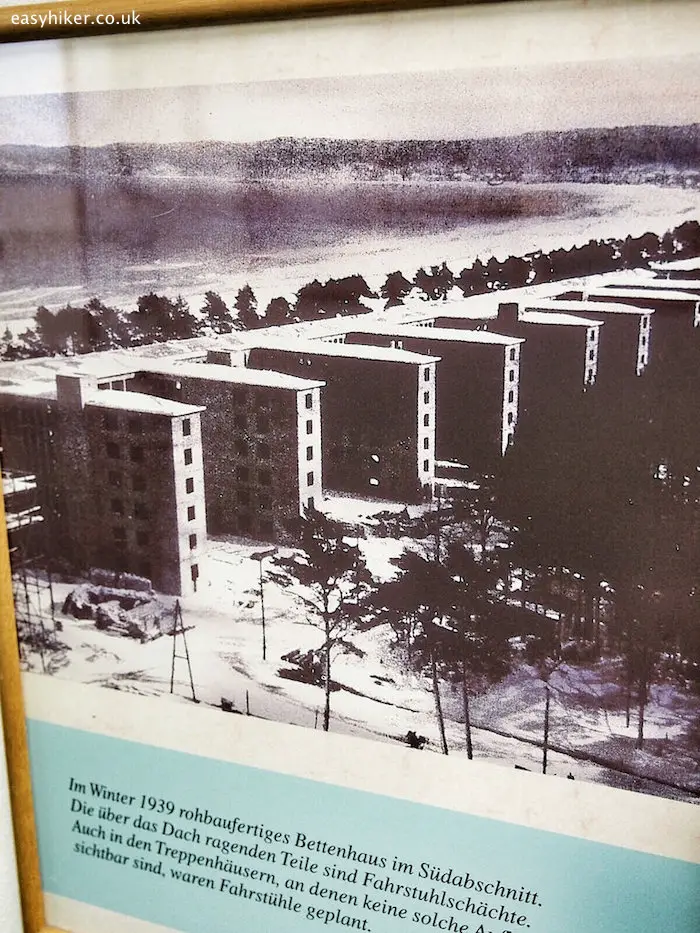

Half a century later, these open stretches attracted a different crowd: those who wanted to make seaside holidays available to the many, not the few. It was here where, in 1936, Nazi Germany embarked upon one of its biggest and most ambitious civil projects: the Prora holiday complex.

Prora was designed as a holiday village for 20,000 people, but the Nazis’ “Strength Through Joy” movement never actually dispatched any families to Rügen’s sandy beaches. When the construction works were abandoned because of the outbreak of WWII, all the accommodation blocks had been finished, but the community areas – for catering, leisure, entertainment, etc. – still remained to be built.

This is why the complex – which still extends over a 2-mile stretch down the beach promenade – looks so finished and unfinished at the same time: a true ghost town, in more ways than one.

After the war, some of the buildings were put to use by the East German army. Only a couple of blocks were ever pulled down (by the Russians, so they could “recycle” the rubble as building material.)

But after 40 years of neglect, Prora looks more than a little jaded. Serious restoration works have started only recently: the first buildings are currently undergoing their conversion into holiday flats (the promotional brochures rather coyly speak of “historic monuments”), which is no mean feat considering their (originally) spartanic interiors.

The overall effect of the complex – especially when you stand in front of those blocks that still await their rejuvenation – is rather numbing.

Prora is also easy to mock – just watch Jonathan Meades in Jerry Building, the excellent BBC documentary on the “Unholy relics of Nazi Germany”.

Still, when we visited the Prora museum (which is located at roughly the half-way mark of the walk through the complex), I could not help wondering how many of the visitors who were viewing the model of the holiday village …

… and who were laughing at its lunatic ambition and Ozymandian scale were aware that this was the birthplace of the very phenomenon that had brought them here: modern-day mass tourism.

The Baltic resorts themselves may be on the genteel end of its range, but it is strikingly obvious that places like Benidorm and Magaluf are little more than an upgrade of the same idea.

Prora is where “holiday man” was conceived as someone with needs for seaside fun, “all-inclusive” deals, partying and … well, little else.

And in the museum, we discovered – among many contemporary documents, newspaper articles (”The Marxists Only Make Promises – Strength Through Joy Delivers!”) and more Prora paraphernalia.

This photograph of another Strength Through Joy (“KdF”) development: a completely new way of experiencing a seaside holiday.

A cruise ship, in other words. That, it seems, was invented by the Nazis, too.