Professional cycling. Don’t you just love it?

You don’t? Too much lycra, too much sweat running down contorted faces, too much time-where-not-very-much-appears-to-be-happening-at-all?

Races remind you of those depression era dance marathons where the last guy standing wins? Of who-can-hold-his-breath-the-longest contests?

Oh well. That is certainly one way of seeing it. But there is another way, too. Plenty of people find professional cycling fascinating, and whatever your view on this may be, there are one or two things that are difficult to deny.

That cycling is rich in history, for example.

Just take the cyclists themselves: the greatest of them are near-mythical figures with names that have lost nothing of their shine in 50 years or more.

If Italian cinema were to make a remake of The Graduate, I don’t know whom they would cast as Mrs. Robinson (although I would strongly suggest the scary whore from that Fellini movie)

But I know who would take the part of Joe DiMaggio in Simon & Garfunkel’s famous theme song. That would be Fausto Coppi. Or Gino Bartali. Perhaps Costante Girardengo. But it would certainly be a cyclist, not a soccer player to whom “a nation turns its lonely eyes”.

And there is something else to say in favour of professional cycling: many of its most famous sites remain accessible.

Just think how difficult or downright impossible it would be to recapitulate in situ the scene where, say, Geoff Hurst scored his World Cup Final hat-trick or where Bobby Thomson fired the shot heard around the world: you would be running around a parking lot these days since both stadiums have long been torn down.

Many of cycling’s greatest moments, conversely, are linked to streets and public places that have changed little through the years and that can be conveniently visited.

How conveniently, however: that depends – like so much else in cycling – very much on the territory. There is a difficult end of the spectrum – the Tourmalet summit, for example, scene of many legendary mountain stages in the Tour de France – and an easy end.

Which brings us to the last kilometres of the Milan Sanremo race.

The last kilometres of this “classic” race – which has been run almost continuously every year since 1907 – are not only easily accessible (the finishing line lies in the heart of Sanremo), but also more “storied” than most, because this is generally where all the decisive moves are made.

The “Primavera” – so called because it is held in the spring, the first major event on the calendar – is a sprinter’s race. At nearly 300 km, it is the longest one-day event in road cycling, but its largely flat route provides few chances of attacking the field and of gaining an early edge.

Which is why, more often than not, the race is decided on those last kilometres down the Via Roma in the heart of Sanremo.

Over the years, a few climbs have been added to give the race more structure, most famously the Poggio (in 1960), a hill approx. 6 km outside of Sanremo.

Our original idea was to take a bus up there (line no. 14/5 from Sanremo bus station in downtown Piazza Colombo) and walk down the final stretch to the finish line.

It turned out, however, that the road on either side of Poggio hill is essentially a road made for cars: there is no sidewalk, and although you can occasionally take cover from the road traffic behind parked vehicles, there are virtually no such parking spaces near the top of the hill.

Up there, you are beginning to think: there must be easier ways of committing suicide.

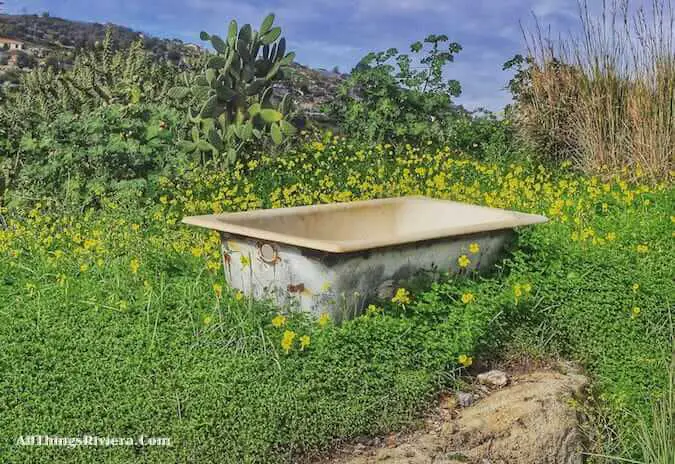

Besides, (and you may take my word for it) the Poggio is not the prettiest sight on the Ligurian coast but an unlovely piece of suburban sprawl, lined with greenhouses and semi-abandoned residential building projects. It is, however, important in the narrative of the race because its ascent provides the climbers with their last chance for an attack.

In 1994, Giorgio Furlan climbed the hill in 5:46 minutes, still the fastest time ever and enough for him to gain a decisive 15 seconds on the field. The descent features 30 curves, including seven hairpins, which makes it difficult for the field to organize the chase of a lone frontrunner.

In 1992, Sean Kelly chased down the leader of the race entirely on his own, “kamikaze” style, gaining five metres in every bend on his Italian opponent before finally outsprinting him down the finish line.

To follow the last 2.5 kilometres of the race, take a bus to the corner of Corso Cavalotti and Via Val d’Olivi which leads up Poggio hill and start walking back (on Corso Cavalotti) in the direction of Sanremo town centre.

This is the posh part of the town, with stately mansions on your left and right …

… and while the riders, jostling for position and trying to work out the battle plans of the other teams, would be far too busy at this stage of the race to enjoy the scenery, you should feel free to peek inside the luscious gardens on either side of the road.

Some of these gardens are owned by the municipal government and free to visit.

The road is straight and flat at this stage, not the perfect terrain for a late attack, but there are always those who try – and some even get away with it.

In 2008, Fabian Cancellara – not a man on whom you would put your money in a “bunched” sprint arrival – started his desperate final attack more or less at the level of the Villa Nobel …

… to become the last “solo winner” of the race until today, if only just. (He was also the first to finish on the Lungomare Italo Calvino by the seaside. In 2015, the finish line returned to its historical site on the corner of Via Roma and Corso Mombello.)

When you arrive at the large roundabout and turn left …

… before following the rightward sweep into Corso Raimondo.

You are then at the spot where the veteran Andrej Tchmil – not considered a grade A threat by the big sprinters in the field – suddenly found himself 20 metres ahead of everyone else and seized the chance of a lifetime, becoming the oldest ever winner of the springtime classic at the age of 36.

And in 2009, the Austrian rider Heinrich Haussler left it even later, waiting for the turn past the famous Sanremo fountain – which provides the backdrop for the TV pictures of the arrival – …

… to “go for it”.

He, however, had left it a little too late: Mark Cavendish, who was still 10m back a mere 100 metres away from the finish line, eventually took the win by a mere 11 cm.

This was not even the closest ever finish: in 2004, Erik Zabel crossed the line with his arms raised in triumph, but the photo finish revealed that Oscar Freire had beaten him after all – by a mere 3 cm.

It may look as though most races are decided in those last ten or twenty seconds when the field enters the home stretch of Via Roma past the fountain, but in fact, the groundwork has often been laid in the previous kilometres.

You can watch footage from recent races here to observe some of these tactics in operation. This can actually be quite fascinating. It will also serve to familiarize you with the territory and be a good overall preparation for the walk.

Professional cycling may be just all sweat and lycra for some, but at least with this walk, you’ll discover more of Sanremo.