The journey to the top of Mount Lycabettus may not fill you with awe, but it will teach you a thing or two about modern Greece

As I said in our last post: Athens is a bit of a strange town inasmuch as nearly everything you see is either more than 2000 years old or virtually new. After a while, you will want to see something completely different from 1970s residential homes and the ruins of antiquity. A mountain, for example? Well then: here it is.

And this is not any old mountain: Mount Lycabettus is the highest peak in Athens, measuring all of 272 metres from top to toe. Don’t snigger: this IS rather a lot, considering that Lycabettus builds up its height virtually from zero (or sea level).

That is also why it is clearly visible from virtually anywhere in town: it always looms over the cityscape, distant and a little forbidding, so you can’t help feeling curious what it will actually feel like over there.

Surprisingly windy: that’s what it feels like, particularly once you are out of the forest and on the “naked stone” part, and overall less forbidding than it looks.

Hiking the highest mountain of Athens

Lycabettus is easy to reach: just take the metro to Evangelismos, one stop to the east of Syntagma Square in the centre of town, and walk through the streets of the Kolonaki district …

… until the stairs turn into a footpath.

The path to the peak is not signposted as such, but you can’t go wrong as long as you follow plain common sense: continue marching forever upward, and try to keep the chapel (on the very top) within sight.

The climb itself of the highest mountain of Athens is actually quite gentle. If you can use a stairway, you can make it to the top of Mount Lycabettus, too.

And for those who cant’t, there is a funicular railway that takes them all the way to the summit.

Suffice to say that if it is the majestic isolation of the world’s great peaks that you are looking for, you will find nothing but disappointment on Mount Lycabettus – it is actually very busy up there, very very busy, tourists freely mingling with Athens’s UN of fitness enthusiasts for whom the wooded slopes of the mountain provide one of the few opportunities of escaping the inner city of asphalt and cement. While the tourists, one suspects, come here mainly for the panoramic views.

But there is one more good reason to come here: because the journey to Mount Lycabettus, the highest mountain in Athens, takes you out of the city centre.

This is one of Easy Hiker’s Iron Rules of city travel: never miss the opportunity of making a trip to one of the more residential areas at your destination. There is always something interesting that you will find out, and, even better, you never know in advance what that something may be.

In Athens, such a journey will inject your travel experience with a dose of hard reality. In the centre of town, with its shiny hotels and well-kept tourist attractions, you might wonder whether all the things you have heard about the state of the Greek economy have been wildly exaggerated.

Crisis? What crisis?

As soon as you step out of the Tourist Athens Bubble, things are beginning to change. Kolonaki, located on the southern slopes of Mount Lycabettus, appears to be a reasonably affluent residential area where, one might presume, the professional middle classes live: civil servants and small business owners.

Once you have factored that into the equation, the sheer number of boutiques, opticians, pharmacies and all other types of shop that appear to have closed recently – sometimes with some of their furniture still inside – can only be described as shocking.

If areas like this cannot support any shops but the most basic ones (groceries, bakers) which ones can? It also makes you realize that many of the shops that still exist must be hanging on by their fingertips.

Once you have been to one of these residential quarters, you will see the rest of the town with other eyes, too. The city’s main department store will suddenly look rather empty of customers, and you will begin to notice that it is mainly the tourists who are eating meals at the restaurants, while the natives appear to restrict themselves to a cup of coffee or a coke.

You will also observe that most cars in the streets are taxis and that the city tour buses are new and spanky, while the public transport system features rolling stock which dates back at least to the 1980s.

Actually, without wanting to sound overly dramatic, Greece looks and feels a little like a country that has just lost a war, with the tourists playing the role of the “occupying army”.

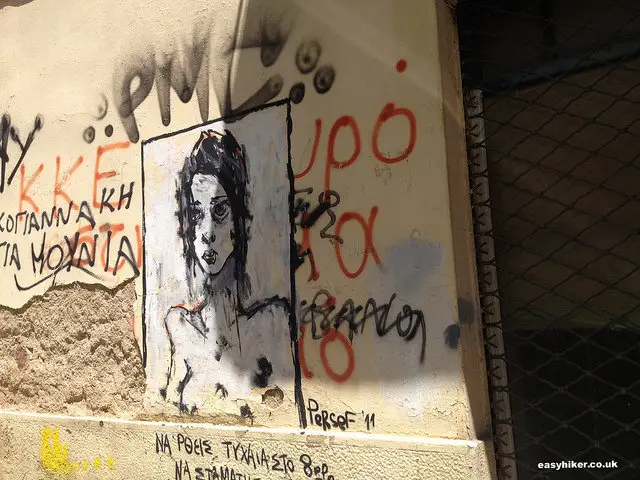

Everything around is geared to their needs: the sites and museums are well-staffed, the streets that connect them are safe and clean, and the hotels look bright and sumptuous, while the Greece of the natives feels tired and neglected, in dire need of a coat of paint or two.

There was something else that shocked me, perhaps because I am old enough to remember Greece as it was in the 1970s. It would have been inconceivable then to have homeless old people roam around the city streets. But today, you can see them on park benches and hunched over a cup of coffee in one of the cheaper establishments, staring into space and seemingly shell-shocked as though they had not yet fully understood what has happened to them.

I am sorry if I have made this all sound rather depressing. Actually, Greece is not a depressing place at all: the people keep their chins up, with a joie de vivre that is typically Mediterranean and a dignity that is typically Greek. And even away from the tourist paths, it is not all doom and gloom, and there are still many interesting shops in business where you can make fascinating discoveries.

Shops such as Grouis, a few blocks away from the Hotel Herodion where we were staying, located on a street called Dimitrakopoulou.

If you go to Athens: make the small detour, it’s only a 5-minute walk from Acropolis Metro station, you will be richly rewarded – particularly if you enjoy candied fruits and the nutty, drippingly sugary sweets of the eastern Mediterranean (baclava and such like).

The shop owner may not be the most naturally cheerful chap in the world – not that he is unfriendly, only there is a certain air of melancholy about him – but his confections have made us and many of our friends (those who received sweet souvenirs) very happy indeed.

Grouis alone is one reason to return to Athens – let’s just hope he can still hang on until then, by his fingertips if necessary.